Sometimes Intense Happiness is the Size of a Linden Leaf

This story starts about a thousand years ago.

In a Chinese pottery workshop during the Song Dynasty, near the city of Chi Chou in China, work processes were well defined and clearly structured. Each step was performed by a specialist. There were separate workers who refined the clay or threw bowls on the wheel. The rough bowls were placed on boards, which when full were removed by the worker responsible for placing pots to dry. When the vessels were leather-hard, another worker trimmed them. After further drying they were glazed and dried again. Finally, the individual bowls were placed in capsules to protect them from the flames, ash and soot in the giant dragon kiln as it was wood-fired over a week’s time.

One worker, who’s only task was to stack the bowls in capsules, made a mistake. He overlooked a leaf which had fallen into one of the bowls. When the kiln cooled, he discovered something astounding. The leaf had melted into the dark glaze and had left a clear, light image of itself in the bowl. It was a useful discovery, a lucky coincidence, something that would be good to replicate. Based on the rarity of these bowls, the attempts to recreate the phenomenon were not particularly successful. Only a very few bowls survived and are now exhibited in Museums or command astronomical prices when they come to auction.

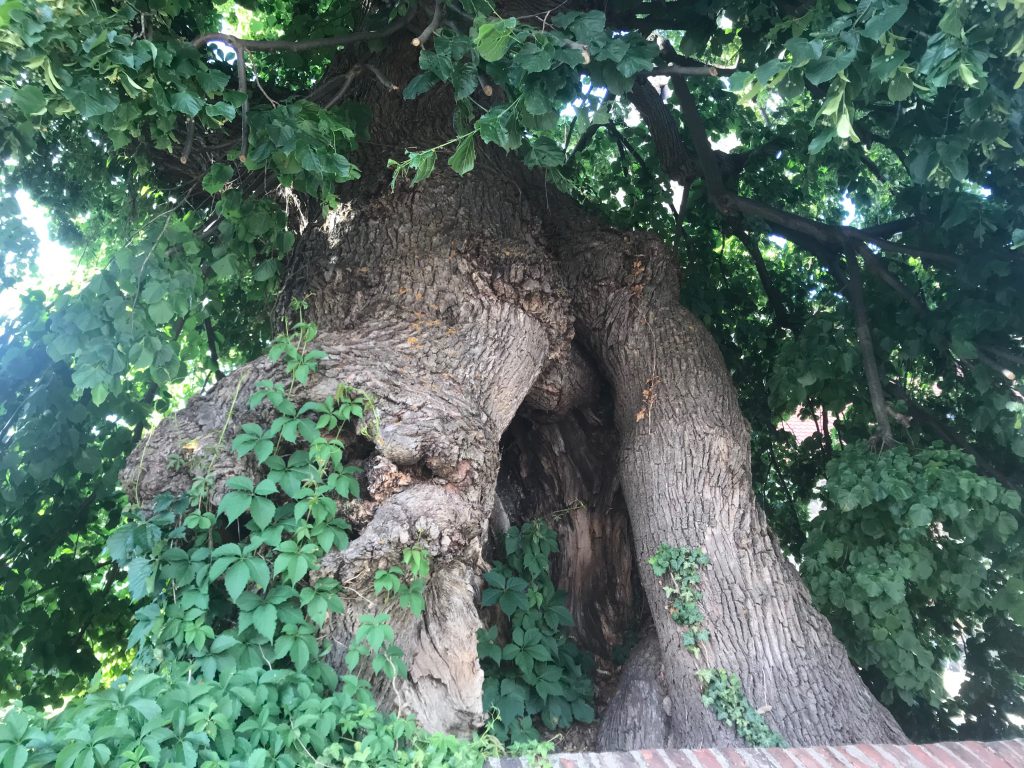

During the Song Dynasty, in what is now the state of Brandenburg a primitive Burgward was established around a stone and timber fortress designed to protect the surrounding slavic farmers village. The villagers planted a sacred Linden tree in the Burgward to honor the Linden Goddess “Libussa”. “Liba” is the slavic word for Linden tree, and they turned to “Libussa” as an oracle in matters of the heart and in questions of justice. At the beginning of the 13th Century, the inhabitants of the tiny settlement also began to build a church. But as they did not place their faith completely in this new-fangled Christianity, they held on to some older traditions. The Linden tree remained in the churchyard and remains there still until the present day.

These stories are held together by one person: me. I live in the village that developed out of the old settlement. I have always been fascinated by the beautiful, timeless ceramics of the Song Dynasty. For years I have tried to unlock the mystery of the leaf motif. Each Autumn when the trees burst forth with their colorful display, I started a new experiment. Unfortunately, I failed consistently. I was able to produce yellowish puddles, or bluish ghostlike, shadows that could be anything or nothing. Not one piece came out with an exact reproduction of a leaf as in the Song bowls.

Last Fall, I couldn’t help but try again. I collected a lot of different leaves, well into Winter when they were rotting on the ground and no longer usable. My studio turned into an alchemist’s laboratory. I maltreated the leaves in every concievable way. I dried them, pickled them and froze them. Countless glaze tests filled every inch of space on shelves and tables.

Every kiln opening was an occasion for disappointment, but I was obsessed with the idea of a positive result. I worked constantly, to the point where I had no room left to put all the ruined test pieces. I always thought I was close to solving the riddle, but after so many failures, I had to accept the fact that I wouldn’t succeed. At the beginning of March this year, I decided to give up.

A day later, I had a new idea – the very last thing I would try, before giving in to defeat – for one last firing.

After the kiln had cooled and I opened the lid and there it was. The first piece I looked at, still too hot to hold: a bowl with the perfect image of a Linden leaf. It was a leaf from the Linden tree in our village, the one that was planted before the church was built, during the Song Dynasty.